Putin’s Spies for Hire: What the U.K.’s Biggest Espionage Trial Revealed about Kremlin Tactics in Wartime Europe

Daniela Richterova

In early 2023, in the sleepy English seaside town of Great Yarmouth, a covert operation was quietly revving into gear. Second-hand Chryslers and a Mercedes Viano van were being transformed into mobile spy units — outfitted with tinted windows, cloned foreign license plates, and kitted out with military-grade surveillance tech. International mobile subscriber identity (IMSI) catchers — devices that mimic mobile towers to intercept phone data — were to be placed into the blacked-out cars and powered by their batteries. Behind it all was a middle-aged Bulgarian man holed up in a cluttered, three-story, former guesthouse, working tirelessly to configure the IMSIs and build hidden cameras disguised as bottles, fake stones, and a birdhouse, which would allow him to monitor the operation in real time.

Soon, he planned to deploy his operatives to ferry the refitted vehicles across Europe. Their destination: Patch Barracks just outside Stuttgart, Germany — an unassuming U.S. military base housing U.S. European Command and Special Operations Command Europe. Their mission: to circle the base for a months-long surveillance operation designed to grab the ID numbers of mobile phones belonging to Ukrainian soldiers. One year into Russia’s full-scale invasion, these soldiers were believed to be training in the operation of U.S.-made Patriot air defense systems. The ultimate goal: deliver targeting intelligence to Putin’s security services, which could be used to kill the operators and destroy the critical missile batteries.

The operation never got off the ground. On February 8, 2023, as the team was preparing to set off for Stuttgart and begin months of clandestine surveillance around the key U.S. base, the plan was abruptly halted. Officers from SO15, Scotland Yard’s elite counterterrorism and counter-espionage command, moved in, arresting most of the suspects in a coordinated sweep across the United Kingdom. By November 2024, six Bulgarian nationals stood before the Old Bailey — the storied London court known for trying the Kray twin gangsters, an ensemble of Cold War terrorists, and the infamous Portland Spy Ring. During the pre-trial hearings, the group’s top three operatives stepped forward, each with a nervous smirk, and pleaded guilty. The remaining three faced a three-month trial. On March 7, 2025, the jury returned its verdict: guilty. The group was convicted of conspiring to collect information that would be directly or indirectly useful to Russia, explicitly referred to as an enemy during the trial, and of endangering public safety and the U.K.’s national security interests.

This was the largest spy ring ever tried in the United Kingdom. I attended the trial alongside two dozen journalists. The 80,000 Telegram messages, financial, travel records, and court testimonies offered unprecedented access to the inner workings of modern espionage networks, providing a rare glimpse into the Kremlin’s evolving espionage playbook. Here is what we learned.

The Contractor Network

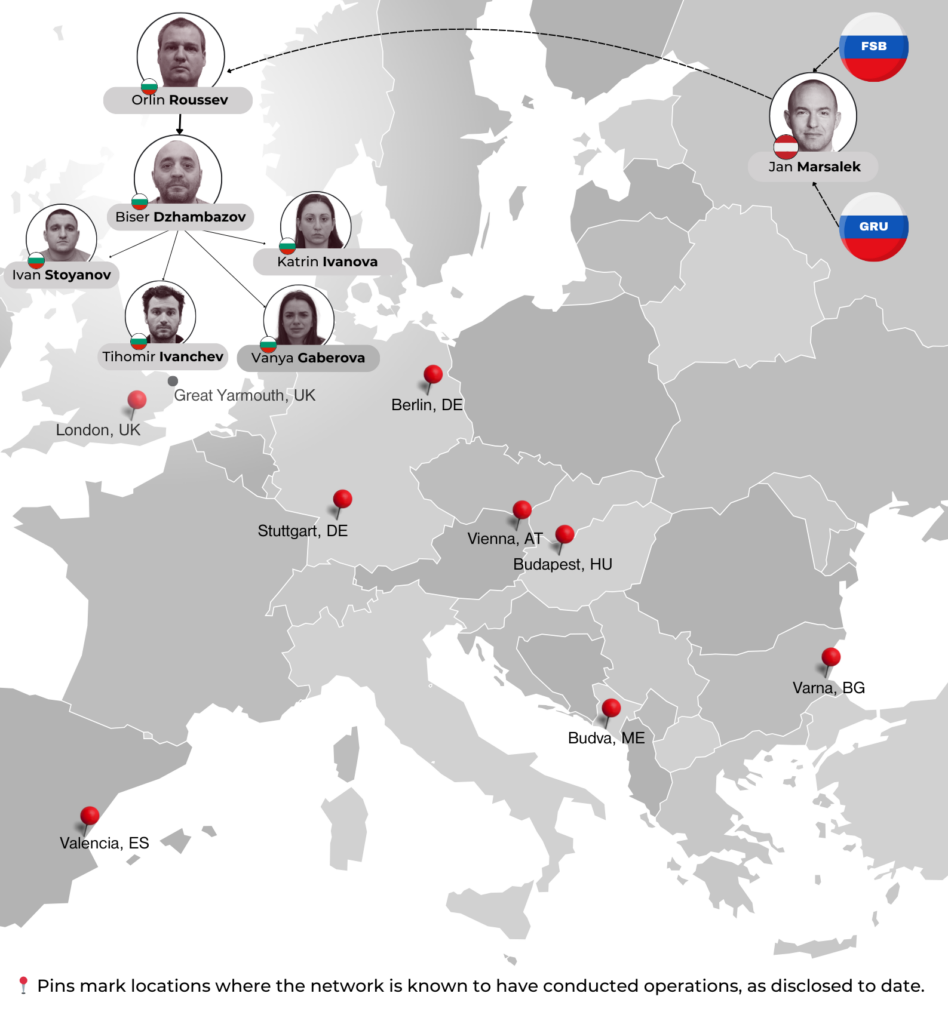

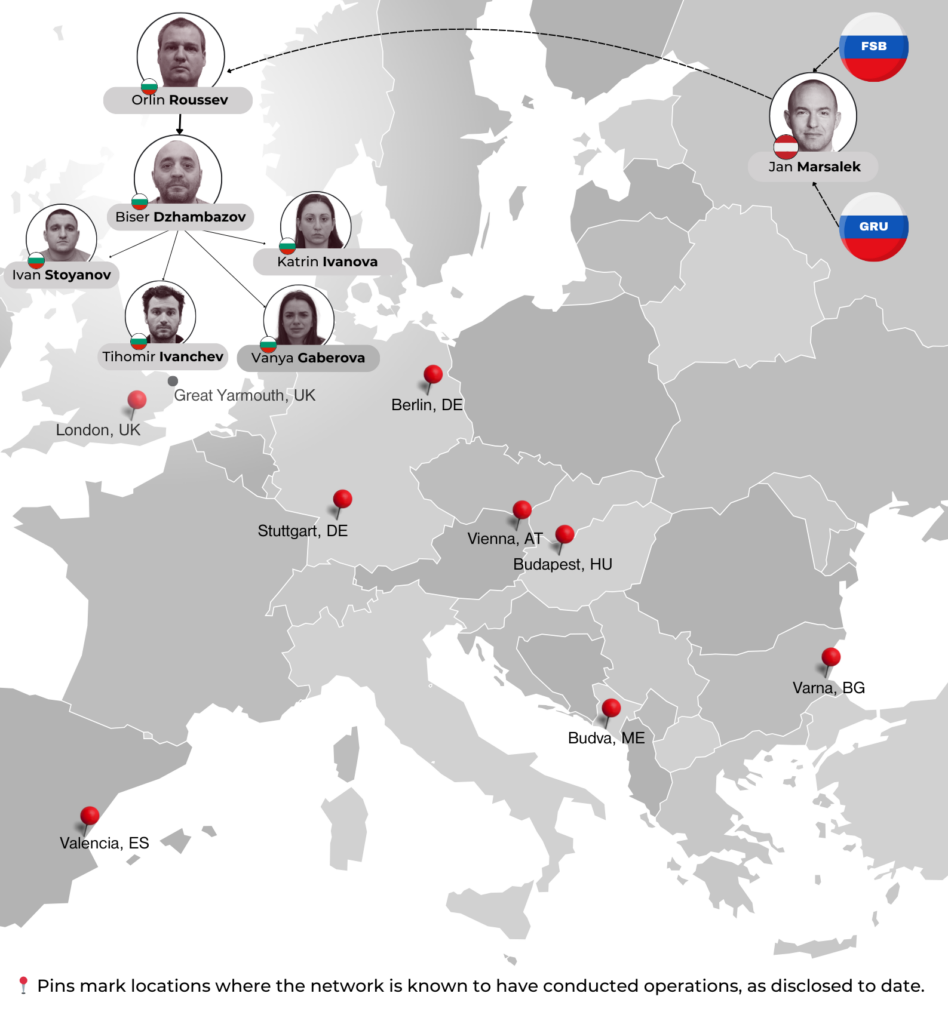

The trial pulled back the curtain on the anatomy of an unusual espionage structure. Rather than a traditional “spy ring,” led by an experienced intelligence officer or “principal agent” — a senior asset trusted with running other agents — the structure exposed in the Old Bailey resembled a state-commercial contractor relationship. In this multilayered, delegated chain, Russia’s domestic security services — the Federal Security Service (FSB) and military intelligence, the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU), now officially known as the GU — acted as the “clients.” According to lead Prosecutor Alison Morgan, they were looking to fill a “gap in the market” that emerged following expulsions of Russian spies shortly after the GRU’s 2018 attempt to poison Sergei Skripal. To fill this need, they outsourced operations to a “contract manager,” Jan Marsalek, the Prada-wearing, disgraced, Austrian ex-Wirecard Chief Operating Officer (COO) believed to be hiding in Russia since the company’s collapse in June 2020. Marsalek, who had pre-existing networks of private operatives and longstanding ties to Russian intelligence, appeared to volunteer for FSB or GRU operations — perhaps as a means to sustain his shadowy business ventures — or to ingratiate himself with the government on whose whims his life now depended.

Acting as a liaison with his Russian clients, Marsalek brought on board a U.K.-based “country manager” — that tech-savvy, middle-aged Bulgarian operating from the cluttered three-story guesthouse in Great Yarmouth. Orlin Roussev, with a murky background in private investigation and IT, had met the Wirecard COO in 2015. By 2020, they were plotting operations on behalf of Russia: Marsalek would bid for covert missions, and Roussev would refine them into detailed operational plans. Together, the pair acted as espionage contractors, fulfilling Moscow’s requests and hustling for the next job.

With the client’s approval, Roussev delegated further operational responsibilities to his close associate, Biser Dzhambazov, who acted as second-in-command or “deputy country manager”. The Bulgarian-born medical courier and community organiser based in the United Kingdom assembled a curious crew of amateur, also Bulgarian-born, “sub-contractors” — individuals who were personally or romantically intertwined — with no formal intelligence training. They included: Dzhambazov’s long-term partner and fellow laboratory assistant Katrin Ivanova; his lover and beautician Vanya Gaberova; her ex-boyfriend, a painter and decorator named Tihomir Ivanchev; and Dzhambazov’s close friend and laboratory colleague, mixed martial-arts fighter Ivan Stoyanov. While Roussev and Dzhambazov planned all operations, typically with Marsalek’s input, the four sub-contractors executed them. Referring to them as the “minions,” Roussev kept them at arm’s length, maintaining a degree of insulation from direct fieldwork.

Image: MET Police; visual by Barbora Ruscin.

Image: MET Police; visual by Barbora Ruscin.

However, at times, Roussev was forced to step out of the shadows — especially when the “minions” struggled to operate the high-tech gadgets he had assigned for each mission. Fashioning himself as “Q” — a nod to the technology mastermind from the James Bond franchise — Roussev assembled what SO15 described as a “spy factory,” packed with hundreds of surveillance and espionage tools. His arsenal included three IMSI catchers, which the jury heard were valued at around $250,000, nearly a dozen drones, and covert cameras concealed in sunglasses, ties, a Coca-Cola bottle, and even a Minion soft toy. There were also Wi-Fi and GPS jammers, bug detectors, eavesdropping gear, vehicle trackers, and an ID card printer, alongside counterfeit passports and driver’s licenses from nearly a dozen European countries.

This equipment gave Marsalek’s contractors the means to conduct surveillance, identity theft, and collect intelligence in multiple countries, and they were all paid handsomely for this work. Records show Dzhambazov receiving a sum equivalent to $215,000, which he distributed to other network members. The hefty rewards received by Roussev’s sub-contractors are in stark contrast with the paltry amounts paid to so-called gig-economy agents-saboteurs — online recruits hired by Russia to conduct high-risk, one-off surveillance and sabotage operations across Europe.

While well paid, the ring was rife with romantic entanglements and personal drama. Dzhambadzov and Ivanova were in an open relationship, but he secretly began an affair with another member of the spy crew, Vanya Gaberova. To further complicate matters, he also recruited Gaberova’s ex-boyfriend, Tihomir Ivanchev. In a bizarre twist, Dzhambadzov is believed to have faked a brain cancer diagnosis — possibly to cover for his double life and elicit sympathy from his partners.

...

https://warontherocks.com/2025/04/putin ... me-europe/